by Lawrence W. Reed

President James Garfield named his beloved dog Veto. The pooch was a monstrous but lovable black Newfoundland weighing more than a hundred pounds. Congress got the message: A bad or unconstitutional bill would go straight to the Garfield doghouse. (Sadly, none ever did because Garfield served only five months in office.)

The veto itself is a long-established and venerable tool of republican government in numerous countries. Along with term limits, separation of powers, habeas corpus, and more, it counts among the storied contributions the ancient Roman Republic gave the world 25 centuries ago. The term itself comes from Latin and means “I forbid!”

So committed were the early Romans to hamstringing the ambitions of power-seekers that they licensed the tribunes of popularly-elected assemblies to kill a bill from the Senate, and they invested each of the two highest officials in the government (the consuls) with the authority to nix the decisions of the other. The veto helped to constrain activist legislators and preserve the Republic for nearly 500 years.

Inspired by the Romans, America’s Founders baked the power of presidential veto into the Constitution right from its inception—in Article I, Section 7. The President may block a measure from becoming law by returning it to Congress unsigned within ten days of its passage (a “regular” veto) or by simply not signing a bill after Congress has adjourned (a “pocket” veto). A regular veto can be overridden, but only if both chambers muster a two-thirds majority. About 7 percent of all 2,572 vetoes since George Washington were, in fact, overridden.

Writing in the June 8, 2014, edition of The National Interest, author Robert W. Merry noted,

“The presidential veto represents one of the Constitution’s foremost protections against congressional activity that exceeds the bounds of the country’s founding document. Indeed, early presidents generally confined their veto decisions to matters that raised, in their minds, constitutional questions.

To arguments of constitutionality, Andrew Jackson in the 1830s added another justification for use of the veto, namely preserving presidential prerogatives that maintained the proper balance of power between the legislative and executive branches of government.”

A presidential veto is generally accompanied by a message explaining the President’s reasons for rejecting the bill. Some of those messages are mercifully short; others go on for pages and can be either tedious reading or brilliant, quotable masterpieces. The very best ones, in my view, are those that defended the people’s liberties and refused to torture the Constitution until it confessed to powers it never intended government to have.

Accordingly, here are my personal selections of the Top Ten Vetoes in American presidential history:

#10: George Washington and the first Apportionment Act of 1792

Any use of the veto by the first president would naturally assume special significance because of its precedent-setting value in asserting this important executive authority. Washington issued only two during his eight years, but this one was particularly good.

The Constitution provides that Congress shall apportion seats in the House of Representatives according to population. The initial bill that reached Washington’s desk called for one representative for every 30,000 persons in each state but with a special allowance: the eight states with the largest fraction of persons after dividing their populations by 30,000 were given an extra member of Congress. This naturally favored the larger states at the time and would tend to inflate the influence of the Federalists over their smaller-government rivals.

Secretary of State and future President Thomas Jefferson advised Washington to kill the bill and demand that Congress apportion without gimmicks and favoritism. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton was more interested in growing federal power and urged that the bill be made law. Washington wisely sided with Jefferson.

A replacement bill that the President signed in the same year apportioned seats in Congress according to one for every 33,000 persons in a state (not 30,000), a more accurate ratio that avoided the fractional chicanery.

Washington’s two successors, John Adams (one-term) and Thomas Jefferson (two terms) didn’t veto anything.

#9: Franklin Roosevelt and the Bonus Bill

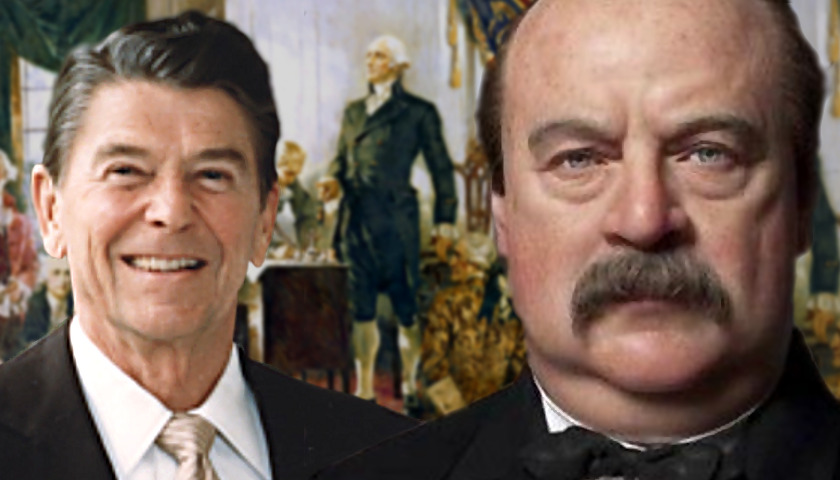

FDR holds the record for the most vetoes by any president, a total of 635. But, of course, he held the office for slightly more than three terms. The record set by any President for two full terms is still held by Grover Cleveland, who nixed 584 bills—more vetoes than those of all the previous 21 presidents combined. And unlike Cleveland’s, a good number of Roosevelt’s vetoes were of bills he should have signed.

Nonetheless, like the proverbial broken clock that’s right twice a day, FDR did a good deed from time to time. One was the day he killed a lavish veterans’ pension proposal called the Bonus Bill of 1935. A vote-buying scheme by his own party, it would have massively and gratuitously increased federal payments to World War I soldiers and their dependents.

In his veto message, FDR offered multiple justifications for his action. Congress had already provided considerable beneficence to veterans. Just over the next ten years under the then-current law, he explained, Washington would be paying veterans $13.5 billion, “a sum equal to more than three-fourths of the entire cost of our participation in the World War, and ten years from now most of the veterans of that war will be barely past the half century mark.” The Bonus Bill would have added billions more.

Some in Congress supported the bill on grounds that the additional spending would stimulate the economy (as if it was manna from the Keynesian heavens). But FDR responded,

“Wealth is not created, nor is it more equitably distributed by this method. A government, like an individual, must ultimately meet legitimate obligations out of the production of wealth by the labor of human beings applied to the resources of nature. Every country that has attempted the form of meeting its obligations which is here provided has suffered disastrous consequences.”

Yes, this is the same President that went on for years thereafter to spend like another famous veteran, the proverbial drunken sailor. On this occasion, however, the time on his personal clock momentarily coincided with that of the clock on the wall.

#8: Andrew Johnson on Removal of Appointees

Sober or not, Andrew Johnson wasn’t much to write home about. However, his veto of the Tenure of Office Act in 1867 (which Congress overrode) was entirely justified and, eventually, completely vindicated. A much-maligned president who didn’t deserve half the mud thrown at him, he deserves praise on this matter.

When Republican Abraham Lincoln put the pro-Union Democrat Johnson on his “National Unity Party” ticket in 1864, he was hoping the choice would win him re-election and help build consensus for a smooth restoration of the Union after the war. He achieved the first objective but not the second. An assassin’s bullet put Johnson in the White House in 1865, and his subsequent relations with a hostile Congress were anything but smooth.

To thwart Johnson, hard-liners pushing a tough stance against the post-Civil War South passed the Tenure of Office Act. It stipulated that the President could not remove an executive official (such as a Cabinet member) whose appointment had been approved by the Senate unless the Senate approved that removal.

The Constitution clearly lays out which officials must be appointed by the President and approved by the Senate, but it is silent on any procedure for firing those officials. By reasonable inference, one can assume that a President can remove an official from the Executive branch and then submit to the Senate the name of a replacement for its approval. How else can a President carry out policy if he’s forever stuck with a recalcitrant, incompetent, or hostile underling?

Johnson vetoed the Act, but Congress overrode him. Then when he fired Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, his enemies in Congress cried foul even though Stanton had been appointed by Lincoln and was clearly insubordinate. Impeachment in the House followed, but by a single vote, the Senate failed to convict and Johnson finished his term. The law was repealed in 1887 and a similar one enacted in the 1920s was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

#7: Calvin Coolidge and Farm Subsidies

My good friend and favorite historian, Burton Folsom, regards our 30th President’s rejection of the McNary-Haugen Farm Relief Act as among the best of a good president’s 50 vetoes. I agree. Coolidge, in fact, killed it twice. See Burt’s analysis here.

The McNary-Haugen bill would have injected the federal government massively into agriculture. Coolidge staved that off for a while, but we eventually got an even worse version less than a decade later in the form of Franklin Roosevelt’s ridiculous and unconstitutional Agricultural Adjustment Act.

Folsom argues that McNary-Haugen “would have fixed prices of some crops by a complicated bureaucratic system and passed the costs on to American consumers.” Even if it had helped farmers, it would have hurt everybody else. Coolidge declared that “Such action would establish bureaucracy on such a scale as to dominate not only the economic life but the moral, social, and political future of our people.”

The federal government has been “helping” the American farmer into bankruptcy for decades with one costly flop of an intervention after another. We should have listened to Silent Cal.

#6: Ulysses S. Grant and the Inflation Bill

The Commanding General of the Union Army and 18th U.S. President was easily the Veto King before Grover Cleveland. While no chief executive prior to Grant had terminated more than 29 bills, Grant killed off 93 of them. Little in his background would suggest financial genius, but he was right on the money issue.

In the latter half of the 19th century, the idea took hold in certain quarters that inflating the money supply was good economics. It would relieve debtors (because they could pay back in cheaper dollars) and stimulate the economy by spurring demand. Never mind what it would do to the credit of the country, the value of savings, or the cost of everything; inflationists of all kinds came out of the woodwork to call for more money, whether it was paper, silver, or chewing gum.

When the Panic of 1873 struck, the Congress succumbed to the money cranks and passed the “Inflation Bill” (yes, they actually called it that). It would have required the Treasury to belch out millions in new paper greenbacks. Grant was a gold-standard man and saw the bill for the threat to the nation’s finances that it was—nothing more than a snake-oil pitch to reduce the value of every dollar in circulation.

Nowadays, the Fed just prints the stuff and nobody gets to vote on it or veto it.

#5: James Madison and Separation of Church and State

Our fourth President, also known as the “Father of the Constitution,” vetoed seven times over the course of his eight-year presidency. Raised a Presbyterian who later dabbled in Deism, he believed that a key to religious liberty was to keep the government out of religion.

The “Establishment Clause” of the First Amendment is unambiguous. “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, nor prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” So in February 1811, apparently reading the words “except every now and then” into the text, Congress passed “An act incorporating the Protestant Episcopal Church in the town of Alexandria in the District of Columbia.” Madison deep-sixed it as a breach of the Establishment Clause.

In the same month, Madison killed a bill that would have granted public lands to a Baptist church in the Mississippi Territory. Congress still didn’t get the message and later passed a bill “To provide for free information of stereotype plates and to encourage the printing and gratuitous distribution of the Scriptures by the Bible societies within the United States.” The President tossed that one into the White House dumpster, too. He knew a slippery slope when he saw it.

#4: James Buchanan’s “Originalism” in 1860

For this one, I draw verbatim from my recent article, “President Buchanan Wasn’t All Bad”:

“In 1860, Congress approved a bill “making an appropriation for deepening the channel over the St. Clair flats in the State of Michigan.” Buchanan nixed it on grounds that would please the most ardent constitutional “originalist.” The bill’s proponents asserted that federal money for the project could be justified as a measure within the federal government’s duty to “regulate commerce with foreign nations and among the several states.” The Constitution does indeed give Congress powers to “regulate” certain things, but Buchanan argued correctly that this does not convey powers to “create.” He admonished,

‘The power to “regulate”: Does this ever embrace the power to create or construct? To say that it does is to confound the meaning of words of well-known signification. The word “regulate” has several shades of meaning, according to its application to different subjects, but never does it approach the signification of creative power. The regulating power necessarily presupposes the existence of something to be regulated…’

To say that the simple power of regulating commerce embraces within itself that of constructing harbors, of deepening the channels of rivers—in short, of creating a system of internal improvements for the purpose of facilitating the operations of commerce—would be to adopt a latitude of construction under which all political power might be usurped by the Federal Government.

That particular veto message was unusually comprehensive and amazingly prophetic. “What a vast field would the exercise of this power open for jobbing and corruption!” he wrote. If Congress possessed a vast pork barrel power (as it has come to possess today), each congressman “would endeavor to obtain from the Treasury as much money as possible for his own locality. The temptation would prove irresistible.” He warned against a system of “logrolling” that could “exhaust” the Treasury.”

It’s pretty clear what Buchanan would think of the spend-happy earmarkers of more recent times.

#3: Franklin Pierce and the Insane

The only U.S. President from the state of New Hampshire, Franklin Pierce cast nine vetoes during his years in the White House, from 1853 to 1857. Five were overridden but not his most eloquent one.

On May 3, 1854, he took great pains (and many pages) to justify his rejection of a bill to grant federal land or the cash equivalent to the States “for the benefit of indigent insane persons.” In the course of performing his Constitutional duty, he confessed feeling “compelled to resist the deep sympathies of my own heart in favor of the humane purpose sought to be accomplished.” He was concerned that he would be misunderstood and castigated as a man without compassion.

One of his reasons for the veto was a profoundly “federalist” one, in the sense of preserving the balance of power between Washington and the rest of the country. “Are we too prone to forget,” he implored, “that the Federal Union is the creature of the States, not they of the Federal Union?”

If there is a role for government to complement the many private efforts and institutions assisting the mentally handicapped, why should the States pawn it off to the distant federal government? And don’t we run the risk, he asked, that “the fountains of charity” might dry up if government at any level gets involved in such things?

Any reader interested in a logical, even (dare I say it) piercing defense of adherence to the “enumerated powers” of the Constitution would do well to read this veto message.

Finally, the President advanced an argument that might draw both chuckles and grimaces today. If Congress has the power to provide for the insane, he said, then, before you know it, Congress will assume it has the power to provide for the sane too! Whether it be, in his words, for grants “to idiocy, to physical disease, to extreme destitution,” or whatever, we should remember this:

If Congress may and ought to provide for any one of these objects, it may and ought to provide for them all. And if it be done in this case, what answer shall be given when Congress shall be called upon, as it doubtless will be, to pursue a similar course of legislation in the others?

Hey, more than a few nations in history have flushed themselves down the fiscal toilet with profligate, publicly-financed, and politicized “compassion.”

#2: Andrew Jackson and the Fed of the Day

If only Woodrow Wilson had possessed a fraction of the wisdom of fellow Democrat Andrew Jackson eighty years previous, America would have been spared such central bank-caused calamities as the Great Depression, seven or eight recessions, and a relentless decline in the value of the dollar.

A backwoodsman and military man, Jackson was no economist, intellectual, or banking expert. But in this instance, hands-down, the backwoodsman and military man was just plain right. On July 10, 1832, he vetoed Congress’s attempt to re-charter its Second Bank of the United States and thereby put politicians and their elitist cronies out of the government-bank business.

The “true strength” of the country and its free economy, Jackson argued, “consists in leaving individuals and States as much as possible to themselves … not in binding States more closely to the center, but in leaving each to move unobstructed in its proper orbit.” He warned of “great evils to our country” that flow from concentrating power in the hands of “a privileged order, clothed both with great political power and enjoying immense pecuniary advantages from their connection with the Government.”

The veto ushered in three decades of relatively “free banking” and economic growth that put America on the world map.

And the Number One Best Veto award (drum roll) goes to…

#1: Grover Cleveland and the Texas Seed Bill

The same President who holds the record for the most vetoes in two terms earns the prize for the single best as well. For a lot of reasons, as I’ve written here, our 22nd and 24th President ranks as a genuinely great one.

When drought struck Texas in the mid-1880s, a majority in Congress thought it was the federal government’s business. So, off to President Cleveland’s desk went the Texas Seed Bill to grab $10,000 from the rest of the country for aiding farmers in the Lone Star State. That was the equivalent of at least two million in dollars of today.

Now, in 2018, the only debate over such a bill would be its stinginess. Not even a $20 trillion national debt would prompt most congressmen to think about the affordability of it, let alone its wisdom on any other grounds. Cleveland took a principled stand, and I can’t say it any better than he can:

“I can find no warrant for such an appropriation in the Constitution, and I do not believe that the power and duty of the general government ought to be extended to the relief of individual suffering which is in no manner properly related to the public service or benefit. A prevalent tendency to disregard the limited mission of this power and duty should, I think, be steadfastly resisted, to the end that the lesson should be constantly enforced that, though the people support the government, the government should not support the people.”

A president who apparently read the Constitution and actually meant what he said when he swore to abide by it—imagine that! Robbing Peter to pay Paul with good intentions? Sorry, said Cleveland; it’s not in there so we can’t do it. What’s a Constitution for if you ignore it? If you think it should be in there, then there’s a constitutionally-prescribed procedure by which you can amend the document. But short of that, don’t make stuff up and expect to preserve liberty, the rule of law, or even fiscal sanity.

Do you think by his statement that the President didn’t care about those poor farmers? Don’t be a sucker. He was thinking not only of the fiscal implication for future generations who might get the bill for it but also the dependable private alternatives already in our midst. He never fell for the lie that politicians are more compassionate than the people who send them to Washington. His veto message continued,

“The friendliness and charity of our countrymen can always be relied upon to relieve their fellow citizens in misfortune. This has been repeatedly and quite lately demonstrated. Federal aid in such cases encourages the expectation of paternal care on the part of the government and weakens the sturdiness of our national character, while it prevents the indulgence among our people of that kindly sentiment and conduct which strengthens the bonds of a common brotherhood.

It took principled courage even in Grover’s day to resist such a measure. Today, it would require a completely different breed of both citizen and congressman than we’ve lately been accustomed to. That’s a sad commentary on us, not on him.”

Of course, the power of the veto isn’t strictly limited to the U.S. presidency. State governors have it, too.

“For these reasons, and not because I love birds the less or cats the more, I veto and withhold my approval from Senate Bill No. 93,” declared Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois in 1949. The bill, formerly dubbed “An Act to Provide Protection to Insectivorous Birds by Restraining Cats,” would have imposed statewide fines on cat owners for letting their pets run “at large.”

Adlai tried twice but never made it to the White House. If he had been elected President, he would have found an environment just as target-rich for vetoes as what was presented him in Illinois.

No vetoes have yet emanated from the pen of President Donald Trump. Before he leaves the White House, I hope there will be many. If he aspires to thwart Congress when it offends the Constitution, I’m comfortable in predicting that there’ll no shortage of opportunities.

I report, you decide.

– – –

Lawrence W. Reed is president of the Foundation for Economic Education and author of Real Heroes: Incredible True Stories of Courage, Character, and Conviction and Excuse Me, Professor: Challenging the Myths of Progressivism. Follow on Twitter and Likeon Facebook.